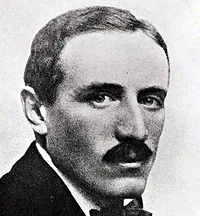

Dr. Xavier Mertz, 1882-1913

Biographical notes

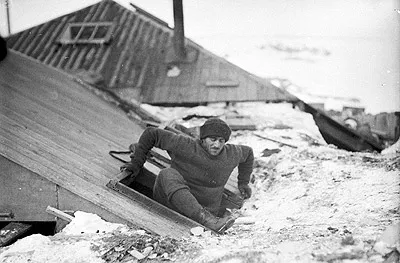

In charge of Greenland dogs - Aurora 1911-1913

6th October 1882 - 8th January 1913

Single, of Basle, Switzerland, a graduate in Law of the Universities

of Leipzig and Berne. Prior to joining the Expedition he had

gained the Ski-running Championship of Switzerland and was an

experienced mountaineer. At the Main Base (Adelie Land) he was

assisted by B. E. S. Ninnis in the care of the Greenland dogs.

On January 7, 1913, during a sledging journey, he lost his life,

one hundred miles south-east of Winter Quarters.

From

Appendix 1, Mawson - Heart of the Antarctic

Xavier Mertz was part of a three man party with Douglas Mawson and Belgrave Ninnis who in the summer of 1912/13 made up the "Far Eastern Party" using dog teams to travel quickly to the east of the expedition base. Disaster struck on the 14th of December 1912 when Ninnis broke through the snow roof of a large crevasse with the largest sledge, strongest dog team and much of the food including all the dog food.

Mawson and Mertz immediately turned back to the base and used the remaining six dogs to supplement their own diet. It is thought that by eating the dogs Mertz became poisoned by the very high levels of vitamin A found in the livers. Both men became ill though Mertz deteriorated rapidly becoming delirious in the evening of the 7th of January, he was found dead in his sleeping bag by Mawson the next morning.

References to Mertz in Mawson's book "The Home of the Blizzard" buy USA buy UK

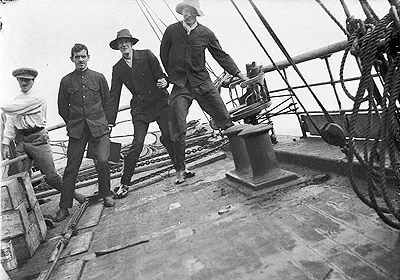

- Before the ship had reached Queen's Wharf, the berth

generously provided by the Harbour Board, the Greenland dogs

were transferred to the quarantine ground, and with them

went Dr. Mertz and Lieutenant Ninnis, who gave up all their

time during the stay in Hobart to the care of those

important animals.

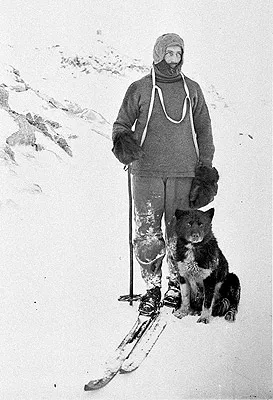

- For several days in succession, about the middle of

February, the otherwise continuous wind fell off to a calm

for several hours in the evening. On those occasions Mertz

gave us some fine exhibitions of skiing, of which art he was

a consummate master. Skis had been provided for every one,

in case we should have to traverse a country where the snow

lay soft and deep. From the outset, there was little chance

of that being the case in wind-scoured Adelie Land.

Nevertheless, most of the men seized the few opportunities

we had to become more practiced in their use. My final

opinion, however, was that if we had all been experts like

Mertz, we could have used them with advantage from time to

time.

- August 1 was marked by a hurricane, and the celebration

in the evening of Swiss Confederation Day. Mertz was the

hero of the occasion as well as cook and master of

ceremonies. From a mysterious box he produced all kinds of

quaint conserves, and the menu soared to unknown delicacies

like "Potage a la Suisse, Choucroute garnie aux saucission

de Berne, Puree de foie gras trufee, and Leckerley de Bale."

Hanging above the buoyant assembly were the Cross of

Helvetia and the Jack of Britannia.

- As the plans for the execution of such a journey had of

necessity to be more provisional than in the case of the

others, I determined to undertake it, accompanied by Ninnis

and Mertz, both of whom had so ably acquitted themselves

throughout the Expedition and, moreover, had always been in

charge of the dogs.

- Mertz was well in advance of us when I noticed him hold

up his ski-stick and then go on. This was a signal for

something unusual so, as I approached the vicinity, I looked

out for crevasses or some other explanation of his action.

As a matter of fact crevasses were not expected, since we

were on a smooth surface of neve well to the southward of

the broken coastal slopes. On reaching the spot where

Mertz

had signalled and seeing no sign of any irregularity, I

jumped on to the sledge, got out the book of tables and

commenced to figure out the latitude observation taken on

that day. Glancing at the ground a moment after, I noticed

the faint indication of a crevasse. It was but one of many

hundred similar ones we had crossed and had no specially

dangerous appearance, but still I turned quickly round,

called out a warning word to Ninnis and then dismissed it

from my thoughts.

Ninnis, who was walking along by the side of his sledge, close behind my own, heard the warning, for in my backward glance I noticed that he immediately swung the leading dogs so as to cross the crevasse squarely instead of diagonally as I had done. I then went on with my work.

There was no sound from behind except a faint, plaintive whine from one of the dogs which I imagined was in reply to a touch from Ninnis's whip. I remember addressing myself to George, the laziest dog in my own team, saying, "You will be getting a little of that, too, George, if you are not careful."

When I next looked back, it was in response to the anxious gaze of Mertz who had turned round and halted in his tracks. Behind me, nothing met the eye but my own sledge tracks running back in the distance. Where were Ninnis and his sledge? - At 9 P.M. we stood by the side of the crevasse and I

read the burial service. Then Mertz

shook me by the hand with a short "Thank you!" and we

turned away to harness up the dogs.

- At 2 A.M. on the 17th we had only covered eleven

miles when we stopped to camp. Then Mertz

shot and cut up Johnson while I prepared the supper.

- January 1, 1913.- Outside, an overcast sky and

falling snow. Mertz was not up to his

usual form and we decided not to attempt blundering

along in the bad light, believing that the rest would be

advantageous to him.

- January 4.- The sun was shining and we had intended

rising at 10 A.M., but Mertz was not

well and thought that the rest would be good for him.

- Mertz appeared to be depressed and,

after the short meal, sank back into his bag without

saying much. Occasionally, during the day, I would ask

him how he felt, or we would return to the old subject

of food. It was agreed that on our arrival on board the

'Aurora' Mertz was to make penguin

omelettes, for we had never forgotten the excellence of

those we had eaten just before leaving the Hut.

- The skin was peeling off our bodies and a very poor

substitute remained which burst readily and rubbed raw

in many places. One day, I remember, Mertz

ejaculated, "Just a moment," and, reaching over, lifted

from my ear a perfect skin-cast. I was able to do the

same for him. As we never took off our clothes, the

peelings of hair and skin from our bodies worked down

into our under-trousers and socks, and regular

clearances were made.

- It was a sad blow to me to find that Mertz

was in a weak state and required helping in and out of

his bag. He needed rest for a few hours at least before

he could think of travelling.

- Late on the evening of the 8th I took the body of Mertz, wrapped up in his sleeping-bag, outside the tent, piled snow blocks around it and raised a rough cross made of the two half-runners of the sledge.

Landmarks named after Xavier Mertz

Feature Name:

Mertz Glacier

Feature Type: glacier

Latitude:

67°30'S

Longitude: 144°45'E

Description: A heavily crevassed

glacier, about 45 mi long and averaging 20 mi wide. It reaches

the sea between Cape De la Motte and Cape Hurley where it continues

as a large glacier tongue. Discovered by the AAE (1911-14) under

Douglas Mawson.

Feature Name:

Mertz Glacier Tongue

Feature Type: glacier

Latitude: 67°10'S

Longitude:

145°30'E

Description: A

glacier tongue, about 45 mi long and 25 mi wide, forming the

seaward extension of Mertz Glacier. Discovered and named by

the AAE (1911-14) under Douglas Mawson.

Feature Name: Mertz-Ninnis

Valley

Feature Type: valley

Latitude: 67°25'S

Longitude:

146°00'E

Description: An

undersea valley named in association with the Mertz Glacier/Mertz

Tongue and the Ninnis Glacier/Ninnis Tongue. Name approved 12/71

(ACUF 132).

Variant Names: Adelie

Depression / Mertz-Ninnis Trough

Biographical information

- I am concentrating on the Polar experiences of the men involved.

Any further information or pictures visitors may have will be gratefully received.

Please email

- Paul Ward, webmaster.

What are the chances that my ancestor was an unsung part of the Heroic Age

of Antarctic Exploration?