Ernest Shackleton - Quest

Shackleton - Rowett Expedition

1921 - 1922

The Crew Alphabetically

Argles, Harold Arthur - 1899-1929

- Stoker, joined at Rio de Janeiro

Carr,

C. Roderick, Major - 1891-1971 - Pilot,

assisted with scientific work as the sea-plane was

unserviceable

Dell, James William

- 1880-1968 - Electrician, boatswain

Douglas, George Vibert - Geologist

Eriksen - Harpoon expert, left

at Rio de Janeiro

Green,

Charles John - Cook (ex Endurance)

Hussey,

Leonard Duncan Albert - Meteorologist, assistant

surgeon (ex Endurance)

Jeffrey, Douglas George - Lieutenant

commander, Navigator and Magnetician

Kerr,

Alexander John, Henry - Chief Engineer (ex Endurance)

Macklin, Dr. Alexander Hepburne

- Surgeon, stores and equipment (ex Endurance)

Bee-Mason, John, Charles - 1874-1957

- photographer, left at Madeira after chronic seasickness

Marr, James William Slessor - Boy

scout and cabin boy

McIlroy,

Dr. James A. - Surgeon (ex Endurance)

McLeod,

Thomas Frank - Able Seaman (ex Endurance)

Mooney, Norman Erland - Boy

scout and cabin boy, left at Madeira after chronic

seasickness

Naisbitt, Christopher - Cooks

assistant and clerk, joined at Rio de Janeiro

Ross, G. H. - Stoker

Shackleton, Ernest H. - 1874-1922

- Expedition

Leader

Smith,

C. E. - Second engineer

Watts,

Harold - Wireless operator

Wild,

Frank - Second in command, led the

expedition following Shackleton's death (ex

Endurance)

Wilkins, George,

Hubert - Natural historian and photographer, joined

at Montevideo

Worsley,

Frank Arthur - Hydrography, sailing master (ex

Endurance)

Young, S. S. - Stoker,

joined at Rio de Janeiro

Query - Dog, mascot - washed

overboard and drowned 9th June 1922

Questie

- Cat - mascot - presented as a kitten by the Daily

Mail

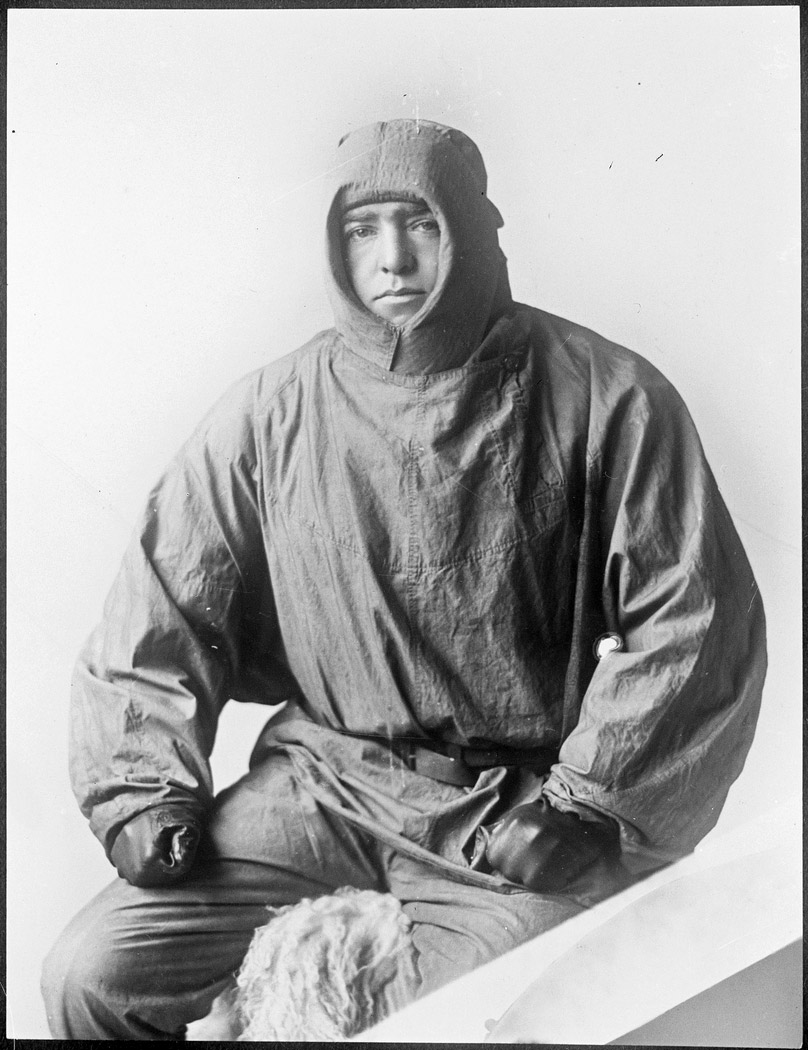

Shackleton in cold weather gear,

a promotional picture for the expedition

Shackleton in cold weather gear,

a promotional picture for the expedition

Shackleton had planned to go to the Arctic on an expedition financed by private individuals and the Canadian government, though they all backed out leaving the expedition close to collapse when British businessman and former school friend of Shackleton, John Q. Rowett stepped in with financial support.

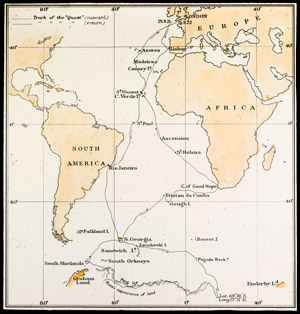

It was now too late for the Arctic season due to delays and so a programme for a very ambitious two year Antarctic expedition including a circumnavigation and the exlporation of some little known sub-Antarctic islands was proposed instead.

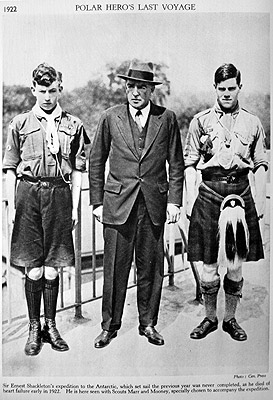

Eight shipmates from the Endurance expedition signed up for the expedition along with James Dell who Shackleton knew from the Discovery. There were thousands of applicants for the remaining places, such was Shackleton's fame by now, there were also two Boy Scouts who were selected from 1,700 applicants for the distinction.

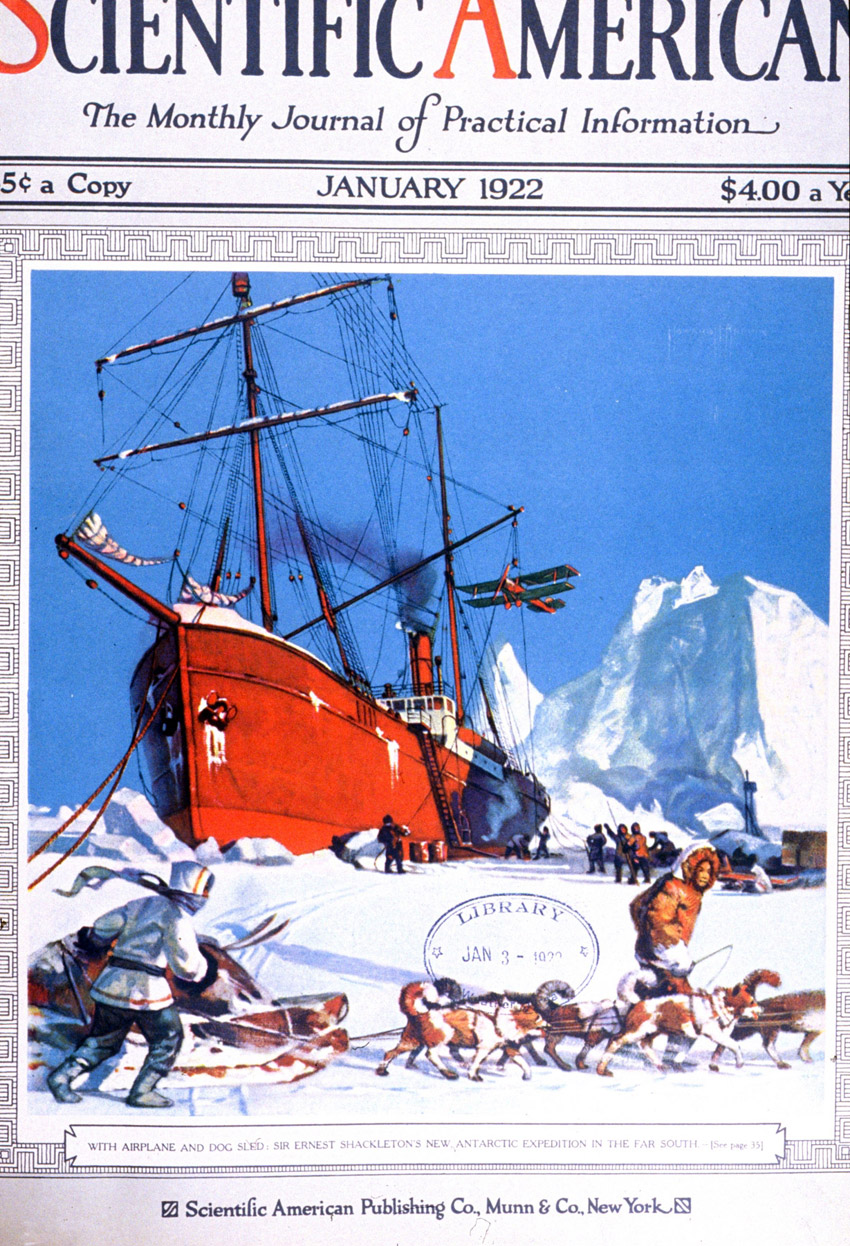

"With airplane

and dog sled: Sir Ernest Shackleton's new Antarctic Expedition

in the far south."

Anticipating the way it should

have been - Scientific American cover picture from the Jan 1922

edition.

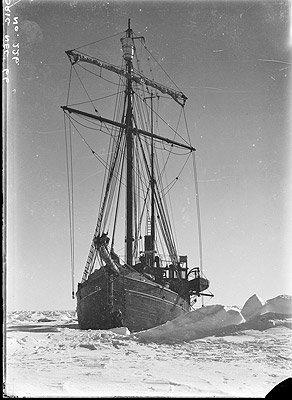

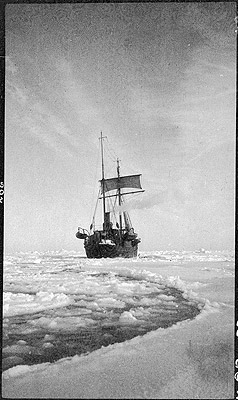

A former Norwegian sealer, the Quest at 125 tons was a small ship, poorly fitted and reckoned to be exceedingly uncomfortable by those who sailed in her. She rolled significantly and moved with the sea making cooking and eating in particular difficult at times. She had a 125 horsepower steam engine, a reinforced bow sheathed in steel and was to carry a small seaplane that would come aboard at Cape Town.

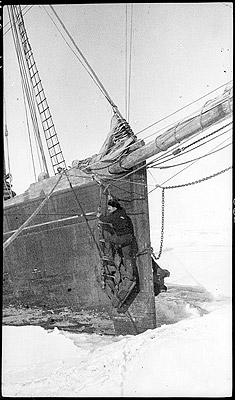

Frank

Wild at the foremast of the Quest, alongside the crow's

nest made from a barrel.

Frank

Wild at the foremast of the Quest, alongside the crow's

nest made from a barrel.

Two of the crew, the photographer Bee-Mason and one of the scouts Norman Mooney were sent home because of chronic sea sickness when the Quest called in at Madeira. They wanted to carry on, but were considered unable to cope sufficiently, even the hardened sailors suffered from some degree of seasickness.

Largely as a result of difficulties with the engine, a month was spent in Rio de Janeiro which led to the plan to cross to Antarctica via South Africa to be abandoned, the sea plane would also now be unavailable. Instead, the Quest would sail to South Georgia and nearby regions.

The constant set backs and difficulties seemed to take their toll on Shackleton both physically and mentally with other members of the expedition noting their concerns in their diaries. On the 17th of December 1921 in Rio, Macklin the doctor was called for as Shackleton "felt a slight faintness", it is thought he suffered a minor heart attack though refused a full medical examination.

The journey to South Georgia was difficult through almost constant bad weather that threw the ship about. There was now a problem with the ships boiler that would have to wait until landfall before it could be addressed. Shackleton became more positive and excited as he came closer to South Georgia, the clouds that had followed him seeming to lift. They arrived at Grytviken whaling station on the 4th of January 1922.

It was to be Shackleton final visit, in the early hours of the 5th of January Macklin was called to Shackleton's cabin complaining of back pains and other discomforts. Shortly afterwards at 2.50 a.m. Shackleton succumbed to a fatal heart attack.

-

I sat up saying 'Go

on with it, let me have it, straight out!' he replied 'The

Boss is dead!' It was a staggering blow.

Wild's diary, 3 a.m.

Sir Ernest Shackleton died suddenly; so suddenly that he said no word at all with regard to the future of the expedition. But I know that had he foreseen his death and been able to communicate to me his wishes, they would have been summed up in the two words, “Carry on!

Frank Wild

Wild was now the leader of the expedition, the news was sent to Lady Shackleton and Rowett. The doctor performed an autopsy finding the cause of death to be coronary heart disease, the hardening of the arteries that supply the heart. Shackleton's body was taken ashore and laid in the whalers church. Wild planned to send the body back to England assuming that this would be his wife's wishes. Hussey was to accompany the body.

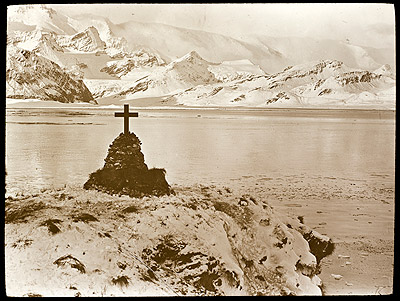

Hussey reached Montevideo (Uruguay) where a memorial service was held, it was here that a message was received from Lady Shackleton. She felt that it was more fitting that her husband was buried on South Georgia. The Quest had left for the Weddell Sea on the 18th of January, long before Shackleton's body returned. He was buried on the 5th of March 1922 at Grytviken at a ceremony attended by the the managers of the five whaling stations on South Georgia and a hundred whalers and seamen. Hussey was the only former companion present at the burial.

Back on board the Quest, not having been able to collect equipment and stores at Cape Town was severely limiting what the expedition could do. Wild in agreement with the other members of the party decided to explore the Weddell Sea, being determined to carry on. Clothing, stores and provisions had been obtained from the whalers on South Georgia. The Quest started to meet ice as she sailed further south, the air turning colder and the sea threatening to freeze as had happened with the Endurance. The Quest reached 67° 17'S with indications that they were reaching the continent as the depth of the sea was decreasing, on the 12th of February however, they turned north again as the ship would not survive being frozen in.

Wild decided to check on Ross's possible sighting of land in the Western Weddell Sea and to visit Deception Island for coal and Elephant Island for seals and blubber and then return to South Georgia. There was a certain discontentment amongst the crew which Wild had to manage, he was keen to avoid any unplanned over-wintering or difficult situation. The Quest was frozen into the ice from the 15th to the 21st of March and for a while it looked like they may have to winter where they were, though they were released. Elephant Island proved an emotional sight for those old Endurances who had last visited it under very different circumstances about five years earlier. A landing at Point Wild where the men of the Endurance had waited patiently for rescue to arrive was not possible due to the weather. Landings on Elephant Island are only occasionally successful due to the frequently difficult state of the sea.

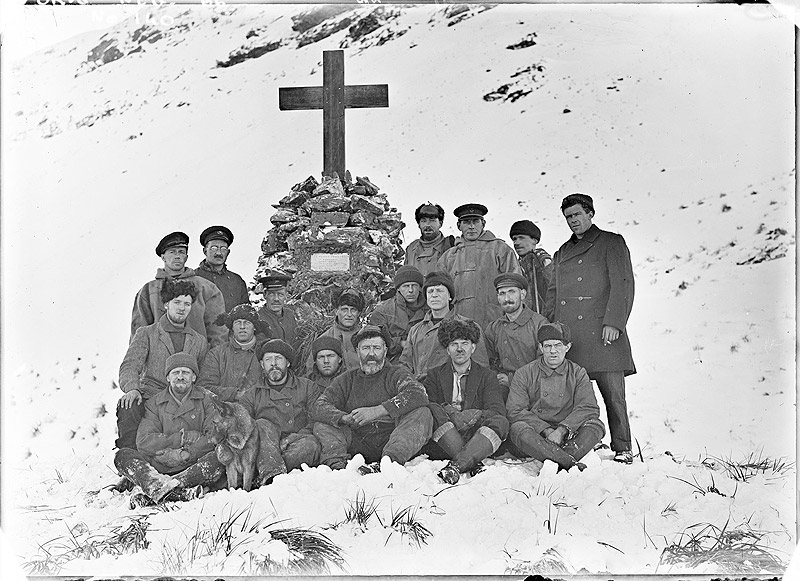

The Quest reached Leith Harbour, South Georgia on the 6th of April. The men of the Quest built a memorial cairn to Shackleton overlooking the entrance to Grytviken Harbour. They departed South Georgia on the 8th of May for Cape Town eventually arriving back home in England on the 16th of September 1922 where they were met by Rowett.

The Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration was over.

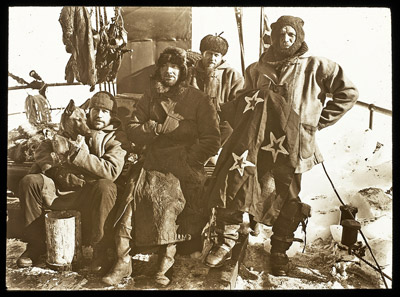

The crew of the Quest

by Shackleton's cairn

The Bell of the Quest:

Provided by - Luigi Casaleggio - Bloemfontein, South Africa

I know that on the 12th of June 1923, The Sons of England

Patriotic & Benevolent Society (S.O.E.) had opened the "Shackleton

Lodge" in Parkview (or Parktown) in Johannesburg and

I have also learnt (from a not-so-reliable source) that

the said Lodge no longer exists.

On (I believe) the

24th of June 1930, Frank Wild donated the ship's bell

from the "Quest" to the Shackleton Lodge.

The following dedication was made at the handing over

of the bell:

"After describing the variety of purposes to

which a ship's bell were devoted in the old windjammer

days, shewing that the bell was the very soul of the

ship, the following is the orientation:- Bell of the "Quest"

I salute you. You were the soul of a ship having a company

of brave men who were seeking lands unknown.

How often have you sounded in storm and calm, in happiness

and sorrow, in sunshine and gloom and in times of hunger

and tribulation. In tropic heat and arctic cold you

have noted the passage of time and also you tolled the

desolation at the loss of your esteemed commander.

I wonder whether this Order of the S.O.E. and Shackleton

Lodge in particular will ever realise the great honour

which has been thrust upon them by giving you sanctuary.

You represent the spirit of our forefather, those

adventurous Englishmen who set forth from London town

and the port of Bristol in their tiny cockleshells of

ships into the wild wastes of oceans for lands unknown

and having found those strange lands there they planted

the flag.

By such methods were built this great

heritage of ours, the British Empire, which has set

the measure of justice and probity for the whole world's

example. Bell of the "Quest", symbol

of race and empire, may your resonant notes ever serve

to remind us of these Englishmen of old whose daring

exploits on land and sea made the Empire to which it

is our proud privilege to belong. May you prove an incentive

to this Order of the S.O.E. to unceasingly endeavour

to bring happiness to this fair land and also to persist

in its efforts to bury the shroud of racialism so that

both races may in peace and unity progress to a great

futurity."

The Sons of England no longer exist in South Africa.

Biographical information

- I am concentrating on the Polar experiences of the men involved.

Any further information or pictures visitors may have will be gratefully received.

Please email

- Paul Ward, webmaster.

What are the chances that my ancestor was an unsung part of the Heroic Age

of Antarctic Exploration?