Douglas Mawson - Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911-1914 - page 2

Spring arrives, plans for major exploratory trips are put into action, disaster follows and then rescue

In the blizzard, getting ice for domestic purposes

from the glacier adjacent to the hut, Adelie Land

In the blizzard, getting ice for domestic purposes

from the glacier adjacent to the hut, Adelie Land

By November the weather had improved and five separate sledging parties were planned. Mawson led the what was to be the "Far Eastern Trek". He instructed each of the five parties leaving the base to be back by January 15th in order to meet the Aurora that would be waiting for them.

All of the parties had their

tales of difficulties and hardship to tell on their return,

but none was to match that to be told by Mawson himself

when he finally arrived behind schedule and virtually given

up as dead.

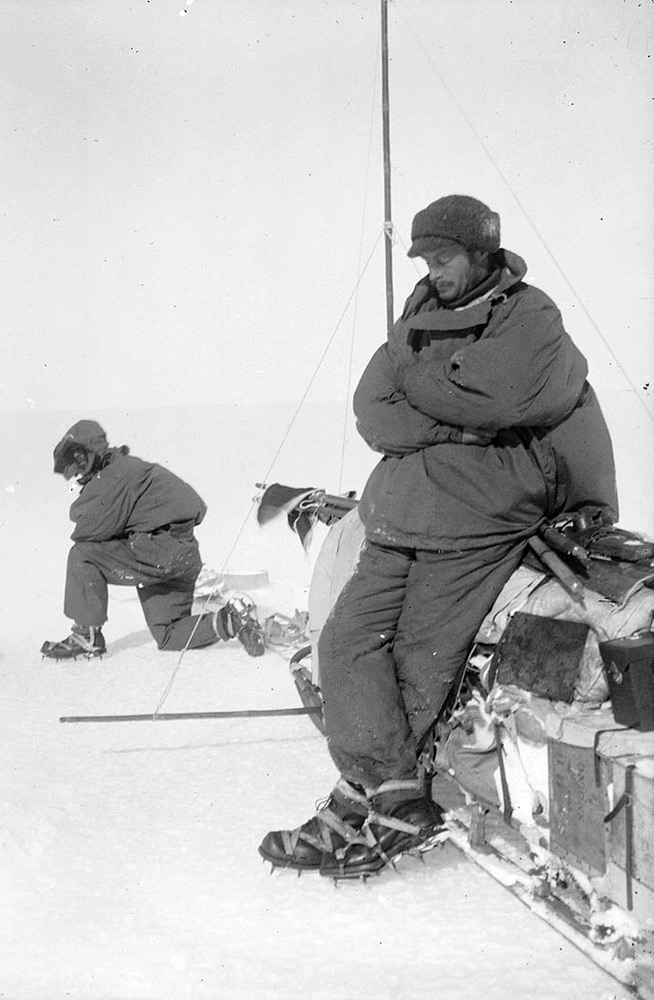

Mawson resting at Aladdins Cave, the outward journey of the

Far Eastern party

Mawson resting at Aladdins Cave, the outward journey of the

Far Eastern party

Mawson set out with two companions, Xavier Mertz and Belgrave Ninnis with a sledge pulled by a team of dogs on November 10th 1912. They made reasonable progress for the conditions, being at times held down for up to three days by blizzards. On December the 14th while crossing an ice field, Mertz in front on skis signaled a snow-covered crevasse, one of many encountered, to be crossed. Such crevasses are hazardous as the snow bridge can be strong or fragile, they are crossed at right angles so as little time as possible is spent trusting to the unknown strength. Mertz crossed first, then Mawson who also made it safely, but then Mertz called out as the third man, Ninnis, his sledge and all of the dogs disappeared from sight. They had broken through the snow bridge and fallen into the crevasse below.

Mawson and Mertz rushed to the edge of the crevasse, and stared down into a deep, gaping hole. About 150 feet below on a ridge was a dog, whining, its back seemingly broken. Beneath this was only the dark open void of the crevasse. Mertz and Mawson called into the depths for over three hours. They gathered all the rope they had but still could not even reach as far as the dog. As well as the loss of their companion Ninnis, they had also lost the sledge, the six fittest dogs, most of the indispensable supplies, the tent, and most of the food and spare clothing. The remaining sledge had only 10 days of rations for the two men and nothing for the six dogs, they were 315 miles from the main base at Cape Denison.

In a few terrible moments with

no forewarning or chance afterwards of being able to do

anything about the situation, they had lost a man and their

circumstances had changed irrevocably for the worse.

They did however have a spare tent cover, but no inner tent or poles, and they had the cooker with some fuel. They had laid no depots on the outward journey as they had expected to take an easier route back to Cape Denison. Some days earlier, they had discarded a sledge in order to travel lighter. They now made their way back to this and reassessed their equipment disposing of everything not essential.

A tent was improvised by draping the spare tent cover over skis and sledge struts. The dogs were fed worn-out finnesko, mitts and rawhide straps. The day after Ninnis was lost, December 15th, the weakest dog was killed to feed to the others and the men. This pattern was continued over the next 10 days until the final dog collapsed. Stringy and tough though the meat was, every scrap was eaten even including the paws - stewed to make them more edible. Ten days later on Christmas day they were still 160 miles from the base. They travelled very slowly managing to struggle on only a few miles per day, their diet was one of dog meat, they were saving the meagre sledging rations as long as possible.

They made very slow progress managing about 6 miles a day most days, on December the 30th however they managed 15. The day after Mertz asked to come off the dog-meat diet and eat some of their remaining sledging rations. Within another day, by the 1st of January, 1913, Mertz developed stomach pains and by the 2nd his strength was nearly gone.

They rested on the 5th and the next day they tried to continue, though Mertz was deteriorating. He agreed to be hauled on the sledge by Mawson and even had to be helped in and out of his sleeping bag. On January the 7th a hundred miles southeast of the Main Base, Mertz became delirious and died.

Left alone, Mawson wrote;

For hours I lay in the bag, rolling

over in my mind all that lay behind and the chance of the

future. I seemed to stand alone on the wide shores of the

world...My physical condition was such that I felt I might

collapse at any moment...Several of my toes commenced to

blacken and fester near the tips and the nails worked loose.

There appeared to be little hope...It was easy to sleep

on in the bag, and the weather was cruel outside.

Mawson continued to walk back to the base, on January 17th he fell down a crevasse and was only saved by his manhaul harness attached to the loaded sledge which held him suspended. He laboured upwards to free himself only to reach the lip and fall back in. Eventually he managed to struggle back to the surface and escape from the crevasse being completely exhausted in the process. He was now taking around two hours merely to set up camp at the end of the day.

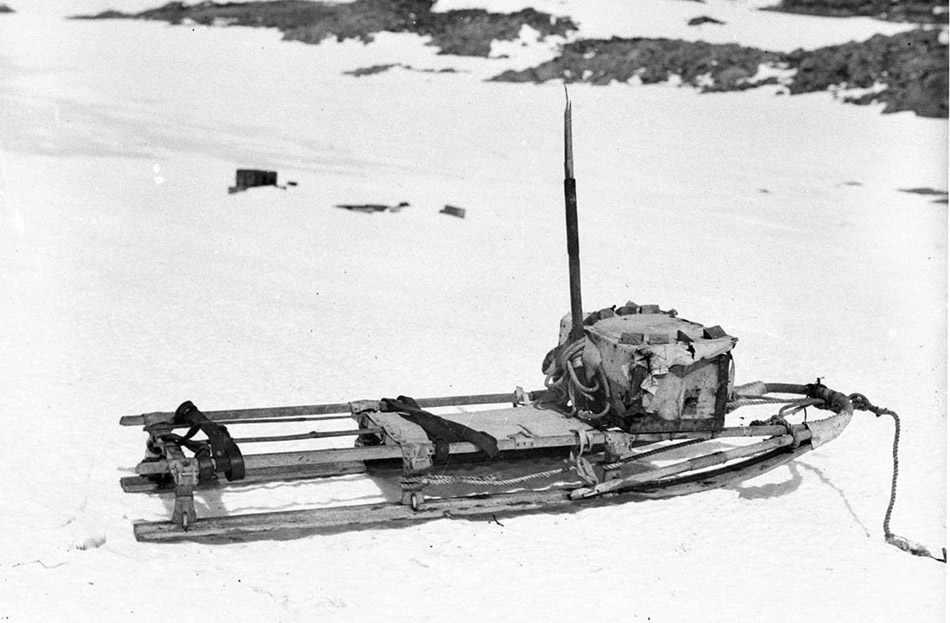

The half-sledge used in the last stage of Mawson's

journey to reduce weight

On January 29th almost completely out of supplies, he spotted a snow cairn built by a search party only a few hours previously. There was food at the cairn and as he ate, he read a note telling that the Aurora was waiting and Aladdin's Cave was only 23 miles away. It still took him until three days later on the 1st of February until he could reach Aladdin's cave. The weather turned once again and he remained there for a further week before he could set off for Cape Denison.

As he reached Cape Denison he saw a departing speck on the horizon - the Aurora leaving Antarctica for the season. Six men however had remained behind to continue the search for Mawson, Mertz and Ninnis and he was greeted as though saved from the dead, which was not far from the truth. They tried to recall the Aurora by radio but ice conditions prevented her from returning and the seven men at Cape Denison resigned themselves to another winter of blizzards and confinement.

March,

soon after completion of the hut, Hodgeman, the night watchman

returning from his rounds outside pushes his way into the veranda

through the rapidly accumulating drift snow

March,

soon after completion of the hut, Hodgeman, the night watchman

returning from his rounds outside pushes his way into the veranda

through the rapidly accumulating drift snow

They were well stocked with supplies however and even made a sledge journey the following spring, on December 12th the Aurora returned. By December 24th, 1913, their two-year expedition was over and on February 5th, 1914 the Aurora set sail for Australia arriving on February the 26th.

On returning home, Mawson

wrote

The welcome home, the voices of innumerable

strangers--the hand-grips of many friends - it chokes me

- it cannot be uttered!

It was later diagnosed that Mertz and Mawson had been suffering the effects of vitamin A poisoning after eating the husky dogs livers.

The Australasian Antarctic Expedition is today regarded as one of the greatest polar scientific expeditions of all times because of the detailed observations in magnetism, geology, biology and meteorology that were made.

Douglas Mawson was appointed Professor of Geology in 1920, he retired in 1952 and died in 1958, the last of the great leaders from the Heroic Era of Antarctic Exploration.

The crew of the Aurora The SY Aurora

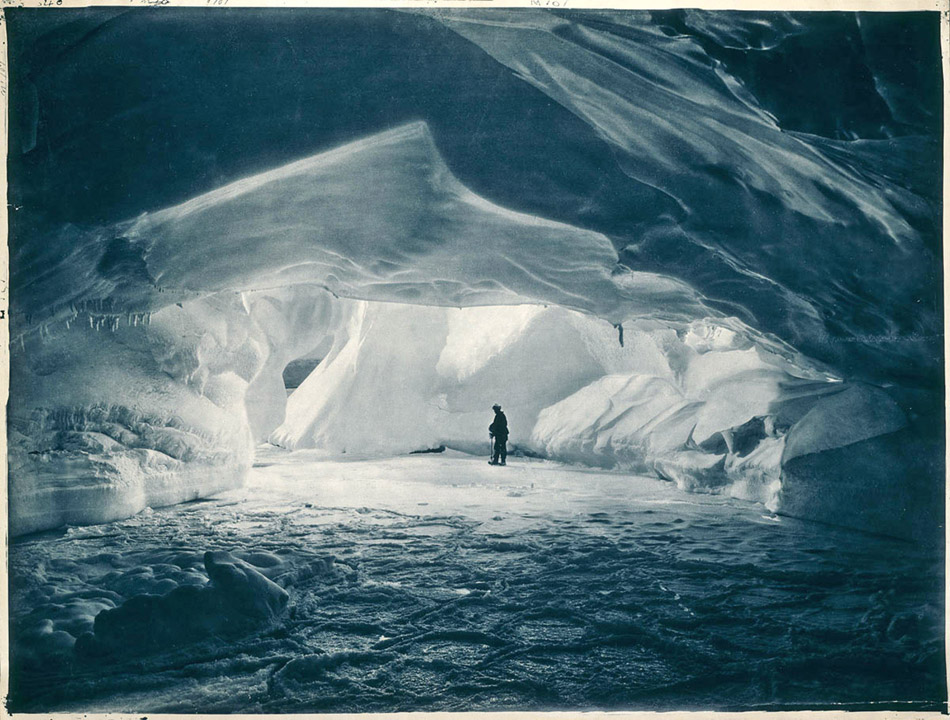

Frozen sea-ice as seen from ice cave at the mouth

of the Metz glacier, Adelie land

Cecil

Thomas Madigan, the meteorologist, wearing an ice-mask, returning

to the Hut during a blizzard

Cecil

Thomas Madigan, the meteorologist, wearing an ice-mask, returning

to the Hut during a blizzard

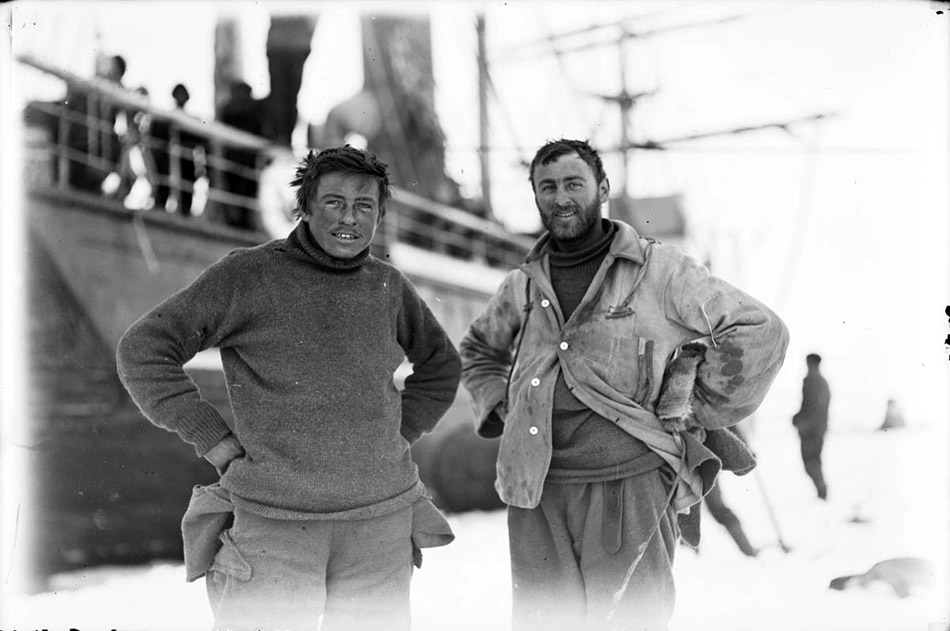

Correll and Laseron, taken on floe ice at the

Western Base

The Western Base Party on the Aurora's deck

The crew of the Aurora The SY Aurora

Douglas Mawson Books and Pictures to Buy

Mawson's Will

The Greatest Polar Survival Story Ever Written - Lennard Bickel

Alone on the Ice

The Greatest Survival Story in the History of Exploration - David Roberts

Racing with Death

Douglas Mawson - Antarctic Explorer - Beau Riffenburgh

Mawson: And the Ice Men of the Heroic Age

Scott, Shackelton and Amundsen - Peter Fitzsimons

This Everlasting Silence

The Love Letters of Paquita Delprat and Douglas Mawson

Home of the Blizzard

Douglas Mawson