Japanese Antarctic Expedition

1911 - 1912

Nobu Shirase

- Kainan Maru

The Japanese Antarctic Expedition led by middle-aged army reservist Lieutenant Nobu Shirase was in Antarctica at the same time and region as Scott and Amundsen while engaged on their attempts on the South Pole.

The Crew Alphabetically

(age) - Place of origin - (dates of

birth/death where known)

Expedition Personnel and Scientific Staff

Hanamori, Shinkichi (33) - Dog

Driver

Karafuto (Ainu)

Ikeda, Masakichi

(45) - Naturalist (second year only)

Tokyo -

(d. 1919)

Miisho, Seizo (34)

- Expedition Hygiene (pharmacist by training)

Fukuoka - (1878 - 1947)

Miura, Kotaro

(25) - Cook (first year only)

Miyagi - (1886-

1967)

Muramatsu, Susumu (26)

- Second Engineer (first year), Secretary (second

year)

Yamanashi - (1885 - 1927)

Nishikawa,

Genzo (24) - Steward

Tottori - (1887

- 1925)

Shirase, Nobu (49) -

Expedition Leader

Akita - (1961 - 1946)

Tada, Keiichi

(28) - Secretary (first year), Assistant Naturalist

(second year)

Okayama (1883 ) - 1959)

Taizumi, Yasunao (24) - Cinematographer

(second year only)

Tokyo - (1888 - 1960)

Takeda, Terutaro (33) - Lead Scientist

Fukuoka - (1879 - 1925)

Watanabe, Chikasaburo

(26) - Ship Crew (first year), Cook (second year)

Gifu - ( 1885 - 1962)

Yamabe, Yasunosuke

(44) - Dog Driver

Sakhalin (Ainu) - (1867 - 1923)

Yoshino, Yoshitada (23) -

Charged with Clothing and Equipment

Hokkaido

(1888 - 1958)

Kainan Maru Ship Crew

Fukushima, Yoshiji (19)

- Seaman

Chiba - (1893 - 1943)

Hamasaki,

Miosaku (28) - Stoker

Oita - (d. 1953.8.3)

Kamada, Gisaku (27) - Helmsman

Ishikawa

Miyake, Yukihiko (28)

- Mate in Training and Translator (second year only)

Kyoto - (1884 - 1965)

Nomura, Naokichi

(44) - Ships Captain

Ishikawa - (1867 -

1933)

Sakai, Heitaro (44) -

Third Mate (first year), Second Mate (second year)

Aichi - (1869 - 1932)

Sato, Ichimatsu

(33) - Helmsman

Fukushima - (1877 - 1959)

Shibata, Kanejiro (20) - Seaman

Aichi - (1893 - 1938)

Shima, Yoshitake

(30) - Purser

Tokyo - (1881 - 1962)

Shimizu, Kotaro (40) - Chief Engineer

Aichi

Sugisaki, Rokugoro (36)

- Stoker

Kanagawa - (d. 1929)

Takagawa,

Sajiro (31) - Seaman

Also goes by name

of Inoue

Tokyo - (1881 - 1937)

Takatori,

Sumimatsu (35) - Stoker (first year only)

Tokyo

Tanno, Zensaku (41) -

First Mate and English Speaker (first year only)

Miyagi - (1871 - 1943)

Tohei, Hirose

(27) - Marine Oiler (first year) Second Engineer

(second year)

Also goes by name of Sasazaki

Chiba - (1885 - 1953)

Tsuchiya, Tomoji

(34) - Second Mate (first year), First Mate (second

year)

Yamagata - (1878 - 1931)

Watanabe,

Kitaro/Onitaro (29) - Helmsman

Ehime

- (1883 - ?)

Yasuda, lsaburo

(32) - Carpenter

Shizuoka - (1880 - ?)

The

Kainan Maru

The

Kainan Maru

In thr early 1900's Japan was coming out of a period of isolationism, and there was little to no interest in polar exploration. Shirase however had been fascinated since he was a young boy and wanted to be a polar explorer initially wanting to reach the north pole though was thwarted in this by Peary in the way that Amundsen was. He had vowed to raise the Japanese flag at the Pole, an intention that made many in Japan who had heard of his ambition wonder what the point was. Like European expeditions, he also intended to make his expedition scientific.

He had little support for his ambitions from the public and the government and the press made fun of his intentions. After struggling to raise funding a former Prime Minister, Shigenobu Okuma came to Shirase's rescue and offered his backing, a single scientist (of sorts) was persuaded to join the expedition. On the 29th of November 1910 Shirase left Tokyo on the small wooden schooner Kainan Maru along with 26 other men and 27 Siberian sled dogs.

His plan was to reach Antarctica in February 1911, overwinter and then make an attempt on the South Pole the following spring towards the end of 1911.

"On 15 September, when the winter will have ended, the party will proceed to the pole."

He aimed to cover 1,400km in 155 days arriving back at the ship in late February 1912. As it was, he didn't reach Wellington in New Zealand until the 8th of February 1911 where he drew great interest from newspaper reporters, the Kainan Maru was easily the smallest ship to try to sail to Antarctica at that time, at 200 tonnes and 30m long it was half the size of Amundsen's Fram and a third the size of Scotts Terra Nova equipped with sail and underpowered with a small engine. Half of the dogs had already died.

He was judged to be poorly equipped and badly prepared, where Amundsen and Scott had substantial, tried and tested Nansen sledges, Shirase had more lightweight sledges made of bamboo, instead of pemmican as the accepted standard high energy sledging food, he had rice, dried cuttlefish, preserved beans and pickles. They were also lacking in basic navigation aids such as charts of the Antarctic seas hoping to pick such things up in New Zealand.

Their biggest issue in this first season however was that they were so late in setting off, they left New Zealand three days after arriving on the 11th of February, after struggling through stormy seas they saw the Antarctic mainland on the 6th of March. They attempted to approach land but the sea-ice was against them so late in the season, Scott's Terra Nova had left 6 weeks previously. After escaping the possibility of the ice closing on the ship and trapping them for the winter (almost certainly a fatal event), they decided to sail north and try again the next year, they sailed into Sydney Harbour on the 1st of May.

Following Japan's military incursions in Russia and China, there was a lot of anti-Japanese sentiment in Sydney, many questioned whether the expedition was genuine at all, the small size of the ship and single surviving sled dog raised questions. Shirase was also considered to have broken the unwritten laws of exploration etiquette, Scott had publically announced his intention to try for the Pole before setting off, this was a rule that Amundsen would also fall foul of when he unilaterally decided there was to be a "race".

Shirase did make allies however and a well to do landowner in a Sydney suburb allowed the team to camp over the winter on his land. Geologist Tannatt Edgeworth David who had returned from Antarctica the previous year having reached the south magnetic pole on Shackleton's Nimrod expedition also came to his aid telling the press Shirase was an genuine explorer and not a spy or secretly looking for new seal hunting grounds as some rumours suggested.

By November Shirase had obtained a new compliment of sled dogs and was ready to head south again. This time there would be no attempt to reach the pole, the crew would focus on surveying and science. He sailed on the 19th of November 1911, by early January 1912 they had sighted the Antarctic mainland, they passed by Ross Island where Scott had his base, on the 19th of January 1912, the Kainan Maru sailed in the Bay of Whales where Amundsen's Fram was moored, Amundsen would be back from his trip to the pole in less than a week.

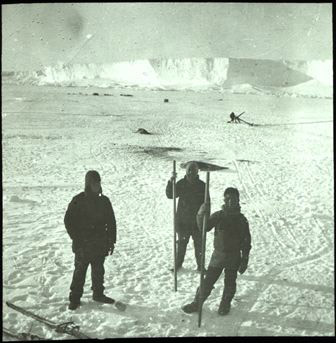

Though he had declared that he was not trying for the pole (and being unequipped to do so) Shirase decided that he would see how far south he could get on a shorter sledging trip. A party of four with dog sleds and supplies for 20 days set off to the south on what Shirase called the "dash patrol". They set off on the 20th of January 1912 battling blizzards and low temperatures and losing some dogs to frostbite in the process, at times they sat out the worst of the weather for several days in their tents. By the 26th, they had only enough supplies for another two days though kept going, after two days Shirase decided it was time to turn back. They had reached 80deg 5' south, the Japanese flag was raised, the emperor saluted and a can containing their names buried at their furthest south point, they then turned back, a journey that took three more days, they had covered 250 km.

While the "dash patrol" was gone, the Kainan Maru dropped seven men off on the King Edward VII Peninsula and continued sailing eastwards on a surveying trip of its own. The seven split into a group of three and another of four and explored in separate directions until they could go no further before returning to the coast and meeting the ship once again. On the 3rd of February all men were aboard the ship and headed for home reaching Tokyo again on the 12th of June.

Unlike his low key, virtually ignored departure a year and a half earlier, Shirase was treated like a hero on his return to Japan. He was soon forgotten again however, largely because he had been unable to secure government backing or support which had delayed his departure so his expedition was eclipsed by Scott and Amundsen.

Shirase now faced the debts incurred by the expedition, he had hoped to be able to sell his story and film footage to pay them off, Japan however was not in the mood for an adventure hero and there was little interest. He died in 1946 largely forgotten and in poverty from paying the debts of the expedition 34 years earlier. There is however now a museum in Shirase's hometown of Nikaho celebrating the expedition. An icebreaker of the Japanese National Institute of Polar Research is named the Shirase after him, though in a roundabout manner, the rules stipulate that an icebreaker must be named for a place, so the ship is named for the Shirase Glacier which is named after Nobu Shirase the explorer.

Shirase Antarctic Expedition Memorial Museum

picture - Mukasora used under CC1 generic, CC2 generic, CC2.5 generic and CC3 unported, Share Alike licences

Members of the Shirase expedition at the Bay of Whales taken by Amundsen's expedition

The scientific results of the expedition were minimal, Takeda the "scientist" had been assistant to a professor and had a string of teaching posts in schools over a short time period, on return from Antarctica he espoused his views on the formation of ice shelves and that the King Edward VII Peninsula was an island, he was incorrect about both. The "unexplored" King Edward VII Peninsula had already been visited by men from Amundsen's party.

Shirase did achieve some successes, his was the first non-European team to explore Antarctica, his "dash patrol" journey past 80 deg south was one of only four groups to have done so at that time. The expedition was carried out on a relatively tiny budget, none of those involved had any previous polar experience and there were no fatalities.